When India opened up their economy in 1991, many hoped that the country’s equality would improve as well. 25 years later, India is still one of worst countries in the world for a woman. Indian universities and parts of the movie world however, offer a couple of oppression free zones.

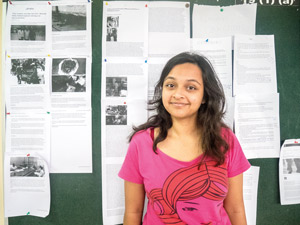

People who stood up in the movie theater and cheered, applauded and cried. That was what Sakhi Shah, a 20 year old law student at National Law School of India, witnessed when she in December went to see the movie Angry Indian Goddesses at a theater in Bangalore.

The movie – which premiered in Swedish movie theaters in July – follows seven Indian women who are summoned to the main character Frieda’s home because she is getting married. So far it may not sound like a very controversial story.

But even before the women meet we get to see that they all have to withstand a high degree of harassment in their everyday life from men in their surroundings – and that they are more than tired of silently putting up with it. After some laughter and friskiness, more and more of the women start to tell the others about their experiences with humiliation. And as the story develops, the flirty and light wedding emotions turn into more darker and unforgiving emotions such as anger and longing for revenge.

When Angry Indian Goddesses was about to go up in Indian theatres last winter it was heavily censured. However, that has not stopped the movie from becoming widely praised by both celebrities and critics, and Sakhi Shah believes that the reason Angry Indian Goddesses has won so many hearts is due to its uniqueness.

“In India we haven’t had stories like this before – stories of women by women. It doesn’t separate women into evil or good but allows them to be both”.

At the same time she thinks it paints a rather depressing picture of women’s situation in India today.

“The way the police react when the women in the movie try to report a crime, and how the only way for them to get justice is to take things into their own hands, that is something I find matches with how I experience reality for us today”, Sakhi Shah says.

India has been ranked the fourth worst country in the world to be a woman in, and the worst country to be a woman in among the 20 countries in the world with the biggest economies. These positions have been given partly because of the frequency of child marriage and trafficking in the country. Scientists estimate that approximately two million women “disappear” in India every year due to female fetuses being aborted, newborn girls being murdered and teenage girls dying from malnutrition.

In 2012, the eyes of the world were on India after a case where a female student was gang raped and murdered by a group of men on a bus in Delhi. However, many people think that this incident was not extraordinary in India. A report from 2014 estimates that every day 92 women are raped in India, and research from 2015 shows that a crime committed against a woman is reported every other minute. Many crimes are believed to never be reported, and there are many cases drawn to attention where women have gone to the police or court to report a crime and instead have been met with sexual harassment, violence or simply have been belittled.

“There are cases where the judge has said ‘But why don’t you just marry him?’ when a woman has reported a man for rape. They assume that the worst thing about the rape is that the woman’s chances of getting married are lowered. But they think that if the man marries her the problem is solved”, Sakhi Shah says.

For a long time, a “two-finger-test” was used in India to determine if a rape had been committed. A doctor would try to insert two fingers into the woman’s vagina, and if it was possible it meant that she had had sex before – and was assumed to have consented to the alleged rape as well. The test has been heavily criticized and has also decreased significantly in use since attention was brought to the rape case in 2012, but it is still used to this today according to rights activists.

Sakhi Shah thinks it is a huge problem in India that justice today is made available depending on your caste, how much money you have, and how much crap you are actually willing to put up with. Living as a student on campus at National Law School of India in Bangalore on the other hand is almost like living in another world according to her. New students at the university are given classes that total three to six hours on what consent means and how to report crime. There is also a board on campus where you can leave complaints if you are subjected to something, and Sakhi Shah says the reports are really taken seriously.

“This way I feel rather free. I can wear what I want, but I often change if I’m leaving campus”.

And the freedom of clothing is something the students at National Law School of India have fought for. In April this year, when a female student was told by her male professor it was inappropriate to wear shorts her whole class reacted by attending the male professor’s class the next day wearing shorts – and standing in the back of the classroom during the whole lecture.

“Those protests went on for a couple of days before the male professor finally apologized. And the university management also announced that they thought his comment was objectionable”, Sakhi Shah says.

V.S Elizabeth, history professor at the Faculty of Law at National Law School of India, thinks that despite this incident you should not count on the students in India to be particularly active in working towards equality in the country in the near future.

“Honestly the students here mostly want a job and lots of money. Many are from the middle class and simply want to graduate and get out of here”, V.S Elizabeth says and continues:

“Sure, more people are angry now and there is a bigger awareness today, but women from the lower castes are too busy trying to stay alive to protest. And even if the middle class protests I doubt it has any effect”.

V.S Elizabeth thinks that the liberalization of India has led to women being marginalized to a higher degree than before. Since the government withdrew the helping hand it earlier extended women now have a harder time to study for example. To create true change for women in India V.S Elizabeth believes that you have to begin at home.

“If you as a boy are raised in an environment where all women seem to be made for you, you will grow up thinking that is the way it is supposed to be. So the question we should ask ourselves is how many women have a leading role in the family. Because if the power relations remain the same within the family they will never change in society as a whole”, V.S Elizabeth says.

It is not possible to speak of one India when talking about such a large and differentiated country, but how conditions vary a lot in different parts of the country – this is something many of the people I interview point. So does Pan Nalin, director of the movie Angry Indian Goddesses. With that said he starts talking about when he travelled around the country and did research for the movie and got to hear a lot of similar stories.

“Many told me about assaults and sexual harassment, and to many it was their first time telling anyone about it. I found it interesting that most of the women I spoke to were first and foremost angry. That even if they started out being sad or tired, after a while that same anger emerged”.

At that time, Pan Nali started thinking about middle class women who are more or less self-providing. He realized that he had never really seen a movie about them in India and decided to make one. He had not anticipated that the movie would draw this much attention.

“Among other things, my actors and I have on several occasions been invited to discuss the movie at different universities in India. It’s really fun, but on some of the tougher questions they ask I feel ‘Whoa, I don’t know, I’m not an expert, I only make movies’”, Pan Nalin says and laughs.

He is very happy with the response, even if he thinks that he did not have any certain intentions with the movie. Even on an international level the movie seems to have stirred emotions. For example, when Pan Nalin heard from a Brazilian movie contact that they wanted to purchase the rights for the movie to be shown in Brazil, the contact also added “and thank you making a Brazilian movie!” to the message.

“’What’, I said, ‘this is a movie about India’, but she responded with ‘you have no idea how well this describes the situation in Brazil!’. So perhaps it’s about more universal topics than I first thought”, Pan Nalin laughs.

Text and photo: Virve Ivarsson

Translation: Elise Petersson