In the latest issue of Lundagård, we had a piece about how some students’ engagement had made them close in on finally burning out completely. Casper Danielsson has seen the new film Yarden (The Yard) and ponders how far we actually are willing to go so as not to be seen as failures.

“Your life is a success story, surely”, a friend of mine bellows in my ear during an increasingly intense pre-party.

“It really is!”

I laugh out loud and quip about how I am going to paint that quote over my bed. The same bed that I had lain in only hours before, in complete apathy during the most part of 24 hours. My friend, let’s call him Alex, continues:

“You have a great job, soon to be exchanged for yet a greater one and a secure future. You don’t need to worry about a thing.”

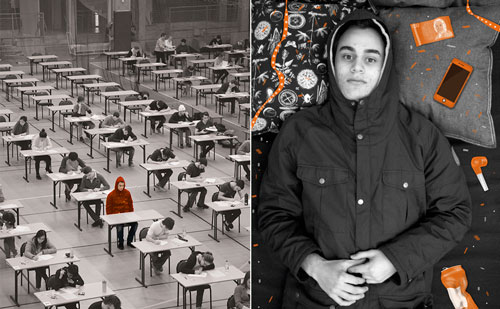

![[Photo: Christina Zhou.]](https://old.lundagard.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/kulturreportagemellan.jpg)

He’s right, but at the same time, so wrong. A year ago, I could only wish for the Instagramified life that Alex is extolling to the skies. Last year, I got a full-time job at Lundagård and that position has, in turn, led to a future employment at an evening newspaper. Something that was everything I wanted, for a long time. Now that I have got it, though, suddenly it counts for nought.

To reach this point, I have juggled two different jobs simultaneously. One during weekdays, the other in evenings and on weekends. For a long time, my goal had been to work at least 60 hours a week – anything less than that would have been a failure. A work week of 80 hours has generally felt like a huge success.

The problem with overworking and burning-out in student life was highlighted in Tindra Englund’s piece in the latest issue of Lundagård. A spex-worker and a nation worker testified that they had been completely engulfed in their engagements, only to come crashing down later on. Although people close to them had told them to slow things down, they did not do so until the problems had grown far too big. When I read the piece, I felt that it might as well have been written about me.

In contrast to the spex-worker and nation worker, what has driven me to work hard has actually never been about desire – it rather stems from anxiety. With a life style completely formed by that, work has often been put first. Last year, I spent Midsummer, Christmas Eve, as well as New Year’s at work. Getting a career has become the only way to reach self-fulfilment, and my predecessor’s jovial maxim “Get published or die tryin’” has been a virtue for me.

It is easy to romanticise a life revolving around work, and even easier to get the confirmation from pop-culture that this is how it should be. Productions from Hollywood like Suits and Billions are perfect examples of how sweet everything seems, as long as you carry on. The characters seem to lead their dream lives, with their work being both prestigious and challenging.

I do not seem to be the only student dreaming about this kind of work. In the Bachelor’s Thesis Framgång, med eller utan karriär – Unga vuxna om karriär i mediabranschen (Success, with or without a career – young adults on having a career in media) from 2015, interviews were conducted with people in the ages 20–30 and they were asked about their views on having a career.

“A majority of those interviewed thought that a career was mostly about personal development – enjoying working somewhere and having a desire to do so. Then, it does not matter if you work 12–14 hours a day,” says Sara Askerlund, one of the authors of the thesis.

For almost a year, I have been told several times that I should go home and do other things than work. Otherwise, they say, it will all go down the drain. But every time I hear it, I have felt, why would I? At work is where I have the best time. It feels more like a piece of advice people give not to seem lazy.

To work is to develop, surely, and I am convinced that it is the number of hours worked that determines how far I can go. If that’s the case I also believe that you’ll have to live with some side-effects such as depression and apathy. I do not find that such problems are reason enough to prioritise something over work.

On the other hand, when I read the previous sentence, it looks as if it had been written by someone in desperate need of help. The sentence feels right, but it looks so wrong. And there is undoubtedly something off with feeling apathetic and depressed as a result of something that is supposed to make you the happiest.

In contrast with Suits and Billions, one series has focussed a lot on the destructive side of career-building – Mad Men, the last season having aired last year. The series revolves around an advertisement agency in New York in the 1960s. The main character is Donald Draper, media planner, who seems to be living the American dream with money, freedom, sex, and power.

At the same time, he is obviously depressed and fills his life with liquor and meaningless sex in the absence of a higher calling in life. “What is happiness? It’s the moment just before you want some more,” Donald Draper states in the ending of season five – a definition dangerously close to my own.

Happiness is the carrot that has long been waved in my face, never quite within reach, but that I never really actually cared about. The last time I can remember feeling lasting happiness for a longer period is the end of upper secondary school. I worked myself to the bone to get accepted to a Swedish footballers’ high school with the very best players in town. Months before the audition, I practiced several times a day in preparation.

Whipped by performance-demands, all that practice eventually led to my wearing down and breaking a bone in my foot, through overworking it. But when I received the acceptance letter, it was worth all the hard work. For about a day. Once I had been accepted and reached my goal, I soon gave up the idea about playing soccer. Suddenly, it was anything but meaningful.

Feeling happy has not been a priority since my teenage years. In my world, being happy has meant being content – and being content is to stop striving for improvement. Therefore, I find that it can be almost fatal to your own development to be happy. On the other hand, I do not wish to be unhappy. What I am most frightened of is getting stuck with a meaningless job, with meaningless things to do, without any inkling of possible advancement.

Exactly that kind of nightmare scenario is described in Kristian Lundberg’s autobiographical novel Yarden: en berättelse (The Yard: an account), the movie based on the novel has premiered in cinemas recently. In the story, we follow the formerly successful journalist and poet Kristian Lundberg, and he gets into some economic difficulties, ending up on the lowest rung of society – being employed in a staffing company in the harbour district of Malmö. Once there, he is reduced to an employee number and fills his work days with moving cars back and forth.

There is something truly terrifying about seeing people in free fall, regardless if they are journalists, media planners, or students. Realising how quickly everything could go down the drain if you are not on pins and needles. Mostly, I have a positive outlook on life, and find pleasure in going to work. The problems occur on the days when that feeling is not present, those days when I fall in too deep and actually cannot get out of bed – no matter how much I would want to work and do what is needed to be able to continue climbing.

Sometimes, I wish that I could turn off that voice inside my own head – a voice other students surely have as well. The one saying that we are all just a few more achievements from reaching our goal. But in actual fact, I don’t think I would ever dare not to listen to that voice. Because, what if it meant that I would be degraded to becoming just another number in one of all the meaningless workplaces.

When it comes down to it, I wonder if it is worth risking it to get that peace of mind. Although it would be nice to actually listen to what my friend says for once when he says that my life is a success story – and getting rid of that conditioned thought that I just need to work for a few more hours to actually make it true.

Author: Casper Danielsson

Translation: Richard Helander