During the Second World War, Sweden was officially neutral. But as the gaze turns inward, the picture becomes muddy. Lundagård is no exception. The newspaper mirrors the moral and intellectual crisis of the time.

An evening in March, Lund 1939. Over a thousand students are pouring into the AF building, and Stora salen is filled to the brim. There is not enough room for everyone, and some have to sit in other parts of the building. Loudspeakers are being moved over for everyone to hear. The topic of the evening is “the import of Jews” – that is, if Sweden should receive eight Jewish doctors who want to escape Germany.

Students from Uppsala have already opposed the proposition. Now, it is time for the students in Lund to have their say.

The list of speakers is long, and only after midnight a decision is reached. Four months after Kristallnacht, Lund’s students put their foot down. Eight Jewish doctors to Sweden is eight too many. The resolution of the anti-refugees is victorious. 724 union members vote in favour of the resolution, 342 vote against.

Before the meeting of the union, lists of names had been put out in Café Athen, urging for a meeting on the issue of refugees. One person to sign was Lundagård editor Gunnar Lorentz. During the meeting, Lundagård was present, reporting that the debate had been “objective” and “dignified”. This in spite of some arguments being pulled from racial biology, and despite the approved resolution being openly racist: “an immigrant causing foreign elements to be adopted by our people is to us evidently harmful and for the future indefensible.”

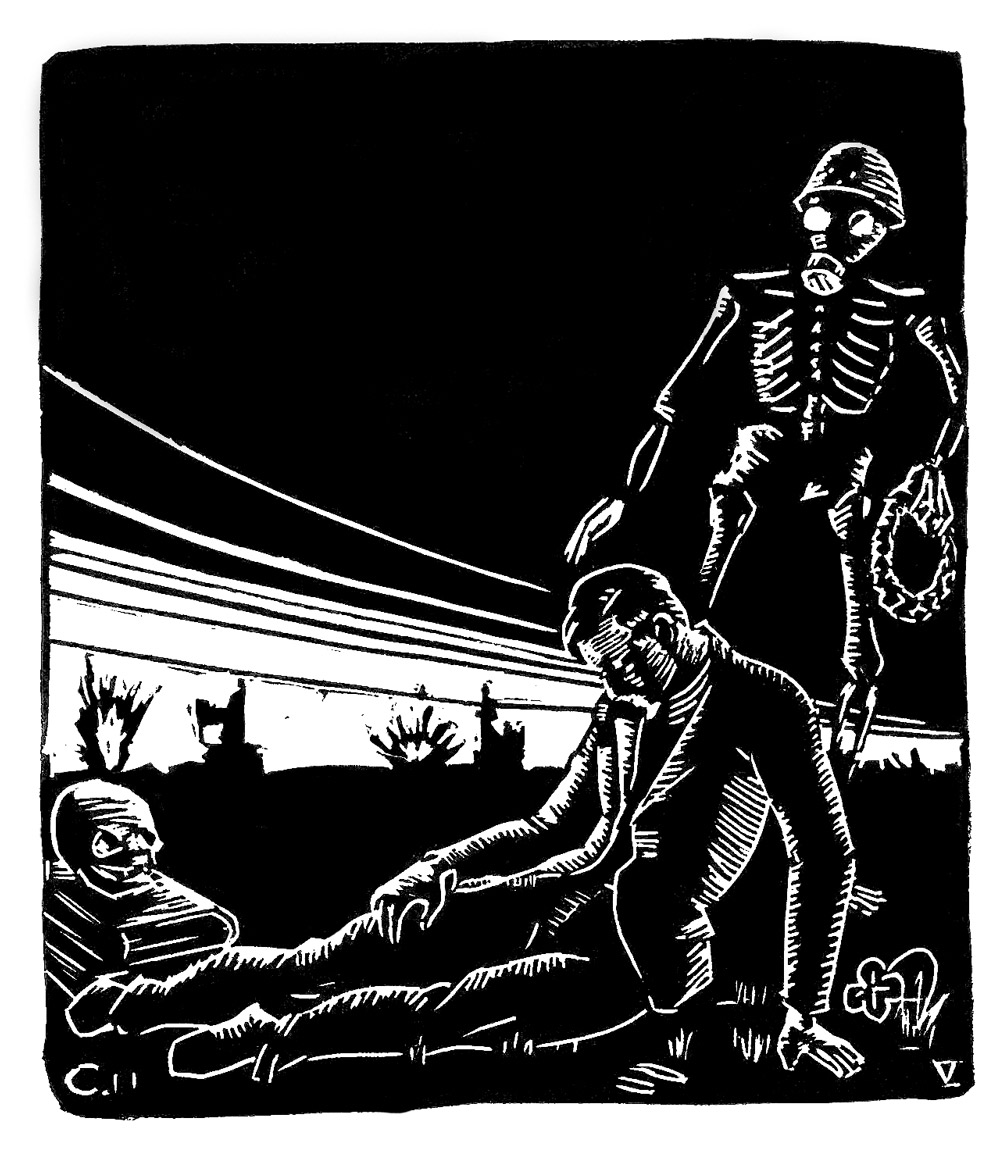

Starting with the national socialists’ accession to power in Germany 1933 and leading up to the meeting of the Union in Lund 1939, Nazism is given an increased space in Lundagård. There is no large scale mobilisation of Nazi sympathies. But at the sidelines of the literary and philosophical expositions, there is a glimpse of a crisis both moral and intellectual within the student life and of clearly brown nuances.

Nordism was a recurring topic. Nazi film director Leni Riefenstahl was revered. In issue 3/1934, one writer claims that the world will “drink health and rejuvenation from the struggle of the German people”. Three issues later, there is a review of a book by Per Engdahl, one of the prominent figures in Swedish fascism.

The critic writes that Engdahl, in a suggestive way, has captured the importance of the nation with the phrases: “The Nation is the common blood”, “The Nation is culture”, “The Nation is a shared fate”.

During the 1930s, the newspaper writes ongoing articles about various organisations, and Lund National Socialist Student Formation, LNSF, is given a column. LNSF’s successful and attractive work is repeatedly emphasised.

A particular success was when Sven Olov Lindholm, leader of the Swedish National Socialist Workers’ Party, came to visit and spoke to a crowded room. When the Minister for Finance, Wigforss, held a speech the following week, only half as many people attended.

That Lundagård had its brown spots is a reasonable claim. But a harsher judgement is hard to pass since the newspaper was not that interested in politics. Lundagård was rather a cultural magazine using substandard echo chamber journalism. Viewing the newspaper as Nazi is further made more difficult by the fact that the editorial staff housed people who would become strong opponents of Nazism.

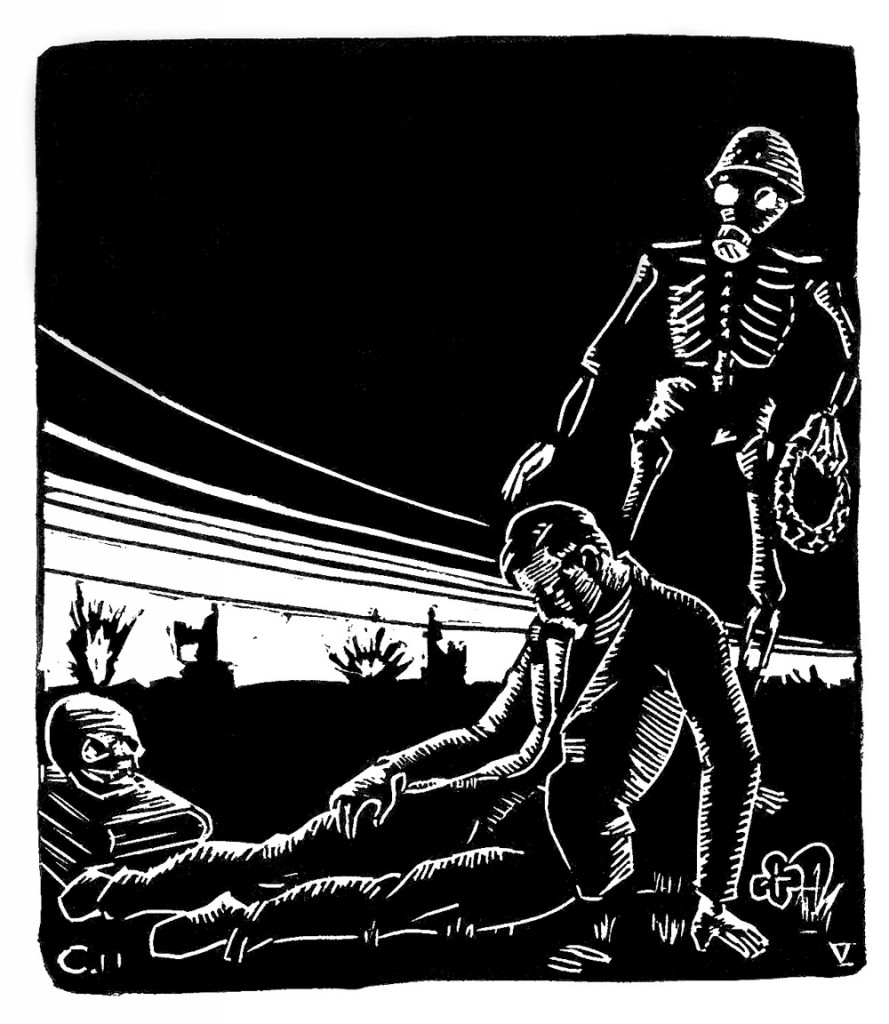

In the recent book Vasakärven och järnröret (2014), culture journalist Per Svensson writes that Lundagård turned distinctly anti-Nazi during the first years of the 1940s. Owing to Per Eckerberg, Paul Lindholm, Jarl Donnér, and Jöran Mjöberg, the newspaper became a “contending, outspoken and, considering the situation at the time, admiringly brave centre for the opposition against Nazism”.

Per Eckerberg is a strong example. A Social Democrat with a past in the left-wing organisation Clarté. He was a member of the editorial staff in 1940, became an editor in 1941. In the appendix for Lundagård’s 80 year jubilee, Eckerberg is said to have been a “red cloth” in some circles. This statement appears to hold. In autumn 1940, his coat was slashed with razors in a dining hall, and at several occasions, he was threatened in pubs by students with Nazi sympathies.

In November 1941, there was a parenthesis in the anti-Nazi history of Lundagård. In what resembled a coup, a new editorial staff was elected that has later been called “crypto-Nazi”. There were much discontent, and in its last issue, the resigning editorial staff heckles the incoming one in a fictitious article. In it, new member of the staff Sten Gagnér (in the article called “Gnäggnér”*) is said to want to “evoke understanding for the folk-Swedish thinking” and he calls the resigning staff for “a people’s front of Anglo-Jews”.

However, the new editorial staff would not last long. In their first issue, an article was published with the intent to protest against the imprisonment of the Vice-Chancellor at Oslo University. It was written by Leif Sandström in consultation with Editor Magnild Rydén. Edits were made by Gagnér and Oscar Bjurling. In a comparison to a pencil going through a sharpener, what came out was claimed only to be fragments of the original. In the end, the article sounded as if it expressed an understanding of the German occupation. Rydén’s editorial staff was forced to resign because of that article.

Those assuming control was a not that controversial compromise staff tasked with repairing the damaged confidence. Not until autumn 1943, the newspaper resumed a political standpoint as Allan Fagerström and Allan Ekberg became part of the editorial staff. Anti-Nazism became prominent once more.

Germany surrendered on the 7 May 1945. In Lundagård issue 7/1945, Editor Berndt Gustafsson wrote about the liberation, and about those who had fallen victims to the executioners of the concentration camps. His closing words ring the bells for the future: “With their suffering, they have made a deposit to the account called humanity, and we must, through aid and modest cooperation, seek to repay what they have given us.”

* From the Swedish word for “whinny”.

Text: Linus Gisborg

Translation: Carl-William Ersgårn